Fame is, like, fucked?

Separate Netflix documentaries on David Beckham and Robbie Williams prove it so.

Robbie Williams is in his underwear.

The chart-topping, globe-conquering megastar props himself up on pillows in bed in his bespoke English manor, where chandeliers dangle in every hallway and giant goldfish swim in the pond outside.

The 49-year-old is about to watch footage of himself as a drunk, coked-up, ultra-cocky teen pop larrikin.

He fidgets, looks away, pinches the skin on his arm repeatedly. “I’m not looking forward to watching what’s next,” he says. “I didn’t have the tools to deal with what’s to come.”

Robbie Williams, the four-part Netflix documentary, is not a celebratory look at the career of the former Take That boy band member who turned himself into one of the world’s biggest pop stars.

Instead, it’s a downward spiral into the dark side of fame.

Holy wow does it get bleak.

Williams hits the space bar on his laptop to watch footage of himself being interviewed before what was set to be his biggest every solo performance, at Ireland’s Slane Festival in 1999.

A TV journalist asks him how he’s feeling.

Rather than excitement or nerves, a young Williams expresses a different kind of emotion.

“I’m really scared,” he says. “I’ve been in a black depression for about the past five weeks. I’m not very excited about much at the minute.”

He doesn’t stop there.

“I’m really scared of it. I’m scared of everything at the minute. I was in bed worrying about it last week. I wouldn’t get out of bed. My confidence has left."

“I’m not really bothered about … anything.”

It’s a call for help, the desperate plea of someone who’s stuck in a bad place and needs someone, anyone to step in and save him.

“I was looking for a bit more of a positive spin,” says the interviewer.

Present-day Williams taps the space bar again. More than 20 years later, with all the accumulated wisdom and life lessons he’s learned, he sums up the situation: “I’m depressed. I’m mentally ill.”

Despite the highs of writing megahits like ‘Angels’, of playing to 375,000 people over three nights at Knebworth Park, of living what seems to be a charmed life with a series of high-profile tabloid relationships, Williams can’t enjoy any of it.

He’s miserable.

His Netflix series is a lot of things, but it is certainly not a pleasant watch. Culled from thousands of hours of behind-the-scenes footage, filmed with present-day Williams watching that footage, it is a sobering look at the perils of fame.

No one seems less ready to cope with life in the limelight than Williams.

He struggles to make friends, can’t hold down relationships, and exhibits paranoid delusions. He turns to potentially deadly cocktails of drugs and alcohol to cope.

Diagnosed with depression at 23, his mental health struggles compound until those three nights at Knebworth in 2003 when he has a full-blown panic attack on stage.

Young Williams is barely coping. And it sets older Williams off too.

“Nobody graduates from childhood fame well balanced,” he reflects. “The years of finding yourself, maturing and growing up that everybody has are taken away from you. It feels like you’re giving more and more of yourself away, to the point where you’re not someone you recognise anymore.”

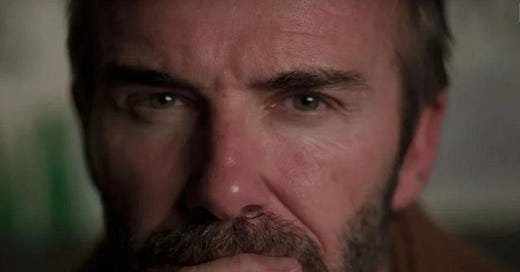

That technique of filming a documentary subject watching footage of themselves like a house of mirrors is also used in Beckham, another sobering series released on Netflix a few weeks ago.

Like Williams, Beckham sits at home alone. Like Williams, Beckham struggles to watch his old videos. Unlike Williams, Beckham stays fully dressed.

He’s a quieter, less forthcoming subject than Williams. Sometimes, his silence on the subject matter – his alleged affair with Rebecca Loos, for example – speaks volumes.

But occasionally, the strains of 90s celebrity shows up full force.

Mostly, it comes from David’s Spice Girl wife Victoria. It’s she who reveals the most, and sheds the tears.

All of it is to do with dealing with the pitfalls of fame. The worst bit? At one point, she was in the stands as a stadium full of football fans chanted, “Posh Spice takes it up the arse,” at her.

“It’s really entertaining when the circus comes to town, right?” she says. “Unless you’re in it.”

Watching these documentaries side-by-side over the past couple of weeks, I was struck by how deeply affected both subjects seem to be by their fame.

Despite being the absolute best at what they do, of being completely untouchable in their prime, of having enough money to do whatever they want, to travel wherever they please, to live wherever they desire, neither Beckham nor Williams seem particularly happy or at peace with themselves and their lives.

Williams whiles away his days in bed, it seems, until it’s time to go on tour again.

Beckham, meanwhile, hides out at his countryside estate, organising his wardrobe for the week ahead, berating his wife for leaving the salt shaker on the bench, and cooking a solitary mushroom on a grill before spending hours cleaning down the kitchen.

The toll fame can take is easily visible. It’s etched into their eyes, faces, and vibes. They say there’s parts they didn’t want. And yet, here they are, inviting cameras into their lives yet again, appearing on the world’s biggest streaming service, ready to kick it off all over again.

Like any drug, fame is addictive. Even now, well past their peak, Williams and Beckham don’t seem to have found a way to kick their habit.

What got you through the week?

I never wanted to be in front of a camera, never wanted to become a media personality, have never aspired to be famous.

Some days I struggle to talk on radio. Other days I stress about having my byline up there on top of this page.

I worry about what I say, what people might misinterpret, what assumptions they might make about me, what could be clipped up and posted on social media to make me look like an idiot.

This week, after sitting through those David Beckham and Robbie Williams documentaries, I’m grateful for one thing: that I’m not famous, and never spent any time chasing something so fickle, and hollow.

Here are some other things that got me through this week…

Cheap concert tickets! Right now, Live Nation is offering discounts on a bunch of shows, including Jonas Brothers, Pink, Queens of the Stone Age, The War on Drugs and, notably after my piece on their VIP ticket prices, 30 Seconds to Mars. You can see the full list of discounted shows here.

Podcasting! I’ve had a lot of requests to appear on podcasts lately, so I said ‘fuck it’ and did them all. Here’s the first one: a chat with NZ Herald’s Damien Venuto for his daily pod The Front Page. The topic? The death of music journalism. I hope it’s not too bleak of a listen for your Friday, but there are things happening in this space: I’ll have more on this next week.

Squid Games! I’m gonna be real honest here: I’m really enjoying Netflix’s reality TV cash-in on its South Korean drama hit. Like, of course they recreated this as a game show. Of course they got 456 people to compete. Of course they make them do Red light, Green light. It’s all just so obvious … and yet, I’m hooked.

Limp Bizkit! What the hell is life? On Sunday night I’m gonna put on my baggy jeans and my Adidas jacket and head along to the nu-metal group’s sold out Spark Arena show to report back. I’m … kinda looking forward to it? Maybe I’ll get in the mosh like it’s 2001 all over again? What is wrong with me?

The St James Theatre restoration! It’s in full swing and you can follow the progress on YouTube with the great documentary series Once Upon a Rebuild. The latest edition details the lengths owner Steve Bielby is taking to find replacements for the statues that were stolen during a break-in last year. Sky World might be falling apart, but at least the St James is making a comeback.

Now it’s over to you. Let me know how you’re going, what’s helped you get through the last seven days, what you’ve been watching, or listening to, or enjoying…

Thanks for supporting my little newsletter. I’ll be back next week. Until then, please consider upgrading your subscription. The more that do, the more I can do.

The last time I saw Glen Hansard perform was at the Auckland Town Hall when, after a stupidly early curfew and classic PA plug-pull by the organisers, he proceeded to lead his band around the room performing acoustically, full-gusto, horn section and all, for a good half an hour more. I saw him perform again this week, and he delivered another soul-lifting performance - complete with a specialist theramin player! - to establish himself as one of my all-time favourite live performers. Magic.