He made the best album of 2024 – but shh, don’t tell him that.

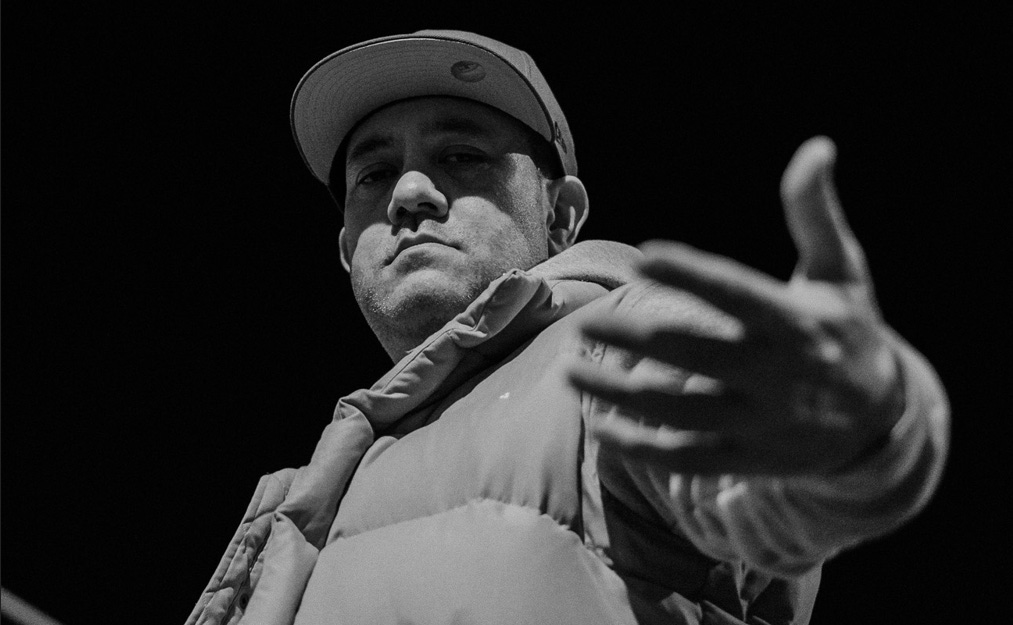

“I’m just some dickhead in a garage,” says Mokotron’s Tiopira McDowell, who couldn't be further from the truth.

When pre-sales opened for Tiopira McDowell’s new album last year, the vinyl instantly sold out. He’d only planned to press 300 copies of Waerea, but they’d been snapped up and his label wanted more. McDowell has a full-time job and two children, and is only able to commit to his music career part-time. So his first instinct was to say, “No”.

He worried he’d end up with boxes of unsold records in his garage. That’s where McDowell makes his music, bass-heavy electronica infused with te reo chants and traditional Māori instruments under the name Mokotron. “My greatest fear is having hundreds of records sitting in my garage,” he says. “It’s an albatross around your neck that you have to carry for the rest of your life”.

Sitting in the shade sipping coffee at a Waterview café, the softly-spoken McDowell stared off into the distance while recounting this story. Released in December, Waerea has been described as the best Aotearoa album of 2024. It is, according to critics, the product of a singular vision, a record that creates its own genre, one McDowell calls an “indigenous bass revolution”. His music is heavy, emotional, and personal, and it affects people: during McDowell’s rare live shows, fans often cry.

Recount all this to McDowell and he goes quiet. He doesn’t understand it. Perhaps he’s being humble, but he talks himself down, calling Mokotron a “novelty act” that’s getting out of hand. “I’m doing something really stupid … who plays a vocoder, a melodica and pūoro over sub-bass?” he says at one point. “I don’t think I have a perception of what the project is,” he says at another.

He’s clearly conflicted, wanting his music to stay as underground and pure as possible without being influenced by external forces. “I think I’m still coming to terms with it,” he tells me. That’s why he shakes his head at all those accolades. McDowell believes he’s better off not hearing them at all. “I see it as a bit far-fetched,” he says. He’s staring into the distance again. “I’m just some dickhead in a garage.”

That garage is in Titirangi where, in 2020, McDowell (Ngāti Hine) purchased a second-hand oak “mandrobe” for $50, opened his roller door, then pushed it inside. On it, he placed two speakers, a sub, a synth and his laptop. Leaning against the wall is an old mattress destined to be thrown out in an upcoming inorganic collection. For now, it acts as a sound barrier, “calming down the early reflections”.

He did all of this on the day he heard of the passing of Reuben Winter, a local producer known as Totems. McDowell began releasing his initial musical experiments in 2011 and 2012, but he stopped when he heard the music Winter was making. “This dude was so good. He was the chosen one … the best Māori producer we’ve ever had,” he says.

If Totems was pushing Māori music forward, McDowell didn’t see the point in doing it too. Then, on September 17, 2020, Winter died at the age of 26. It sparked something instinctual in McDowell, who headed straight to the Rock Shop to purchase an 808s drum machine. The singular thought driving him was: “Someone's got to do it … I’ve got to do it.”

By day, McDowell works as the head of Te Wānanga o Waipapa at the University of Auckland, delivering Aotearoa history lessons for up to 600 people. His classes are so full he has to turn people away. When enrolment opens every November, the website crashes under the load. “It's unstoppable momentum,” he says. “We have no idea how much these young people want to learn te reo and Māori history – we don’t have the teachers to teach them all.”

So, when he gets a few spare hours to work on music in his garage, that surge in cultural support sits in the back of McDowell’s mind. So too does the music he grew up listening to, indigenous acts like Moana and the Moa Hunters, or Australia’s Yothu Yindi. McDowell takes that and his personal experiences and struggles, then funnels them into huge, pulsating soundscapes that require a decent subwoofer to fully experience.

It may hit you in the chest first, but listen closely and you’ll find powerful messages mixed into McDowell’s music too. His songs ask big questions about colonialism and legacies. To make ‘ŌHĀKĪ’, McDowell took on the death of Queen Elizabeth, asking, “Who will take responsibility for returning these lands to us?” He wrote ‘WAEREA’ after his dad’s death as a way of clearing “the lingering effects of trauma and violence”.

It’s dark, hypnotic, occasionally dystopian music, a medley of break beats, dubstep and drum ‘n’ bass. McDowell records his lyrics by shredding his vocal cords to the point he can’t talk. He describes it as “whaikōrero flows … angular breaks, subterranean bass drops … drum n bass on lean”. He could easily dumb it down, he says, and take it overseas. But he refuses to sell out. “I'm not going to fit in,” he says.

Many of the songs on Waerea have their origins back when McDowell first started making music in 2010. He knows now it was too soon to cut through. “It was too edgy,” he says. “It was treated as ‘world music’.” But the groundswell of support for Māori culture, the demand to use te reo in everyday language, and the antics of the current government, means his timing feels just right. All he has to do now is get his head around Mokotron’s growing fanbase.

When we spoke in December, it was a few days after McDowell had recorded a performance for Boiler Room (not my newsletter; the live DJ platform). It was there that he had the first inkling Mokotron might be taking on a life of its own, that it could be “bigger than I think it is”.

It happened when he got a glimpse of the crowd. “They were looking at me differently,” he says. “They were expecting me to be this … presence.”

But McDowell doesn’t see himself that way. He is, he says, still “some dickhead,” just a guy in his garage, making “weird, dark” music when he feels like it. To him, taking it out of that space and playing live creates pressure. It’s why he refuses many festival offers, and turns down most promotional opportunities. “Everything gets generic when you open yourself up to what everyone else is doing,” he says. “The more you're around people, the more you copy them.”

So, unless his hand is forced, McDowell will try to keep Mokotron as secluded as possible. It’s the only way he can make it work. “Isolation creates the most unique shit and that album comes from never leaving the garage,” he says. “The best thing I can do is just stay away, stay in the garage.”

Waerea is out now through SunReturn; vinyl copies are available here.

Music journalism is all but dead in Aotearoa. So thanks for being here and supporting my lil’ newsletter. This can’t exist without readers who contribute to my work. If you’d like to do so, you can use this blue button when you’re next sitting in front of a laptop. Subscribers get every issue, plus bonuses and access to the comments, and that wonderful warm fuzzy feeling that you’re keeping this dream alive…

Chuck Eddy quoting Boiler Room!

https://accidentalevolution.wordpress.com/2025/01/02/150-best-albums-of-2024/

Thank you for this! Love that he’s saying no to all the standard boring promo work and most festivals. Didn’t know the connection to Totems